In a new mayor, NYC's African communities see a chance for renewed engagement

By Tunde Olatunji

Even by its own typically unsparing standards, the ongoing New York City mayoral race has been closely covered. This surge of attention and scrutiny has also brought into focus the experiences of the broad cross-section of communities that call this city home–many of whom go into November seeking greater support against a barrage of challenges that make their continued presence here about as precarious a prospect as it’s ever been. In addition to articulating customary policy positions on taxation and public safety, the campaigns have also been drawn into discussing plans to address what has become a livability crisis for many across the five boroughs.

This is notably the case for the African communities throughout the city that see this election as a unique opportunity for renewed engagement with the mayor’s office. A chance to give voice to the policy and legislative priorities of communities that have long felt the important nuances of their struggles get lost in efforts to simplify the city’s often unwieldy top-line issues. These neighborhoods are composed of people whose families or who themselves hail from all corners of the African continent but who are also, importantly, New Yorkers. Enmeshed in the fabric of city life, their main challenges are not at all dissimilar from others they share the city with—affordable housing, better access to city services, and concern with the welfare of their young people. The intention here is not to assert that any of these issues are somehow unique to African communities in the city, but rather to highlight the important ways that these challenges intersect with how many of these communities are constructed.

(Photo by Rashawn Austin)

The combination of rising rents and a diminishing affordable housing stock has made shelter an increasing uncertainty for far too many who live here. In African communities, the urgency can be particularly pronounced. For those who came here as asylum seekers–many arriving during a spike from 2022 to 2024–the city has largely struggled to absorb them. Families arriving primarily from Guinea, Senegal, Mauritania, and Angola, have endured a seemingly endless pursuit of short-term housing that can often be deeply demoralizing. Research published last year by a consortium of community-based organizations (Afrikana, Make the Road NY, and Hester Street) on the experiences of asylum seekers in the city found that 85% of respondents faced what felt like hasty notices to vacate shelters and a mere 5% reported being able to find alternative housing options. When they were able to secure spaces, 61% of respondents also reported feeling unsafe.

Even if we were to exclude the plight of newly-arrived African migrants to the city, the imperative of affordable housing remains evident in the lives of longstanding African New Yorkers as well. Be it in those belonging to cultures where conceptions of the family unit might be incompatible with the idea of sending aging family members to live in nursing homes, or those for whom an illegally converted basement apartment is the only way to ensure that their family gets to stay under one roof. To the city’s credit, steps have been taken to lift some of this burden including recent policy changes to ease restrictions on constructing ancillary dwelling units, and launching the NYC Housing Connect portal to help residents navigate available options. But a big part of the issue is ensuring that these communities have access to this information as services become available.

(Photo by: Rashawn Austin)

Residents often provide low ratings on the quality of city services. Some of this is rightly due to poor or inadequate provision, but limited public awareness that many of these services even exist is another important factor. Among African communities, this lack of awareness is exacerbated by language barriers that make access to these resources functionally impossible. While the city boasts a recent expansion of its language access program to a total of ten languages–thanks in no small part to the efforts of African Communities Together (ACT), an organization that has long and tirelessly advocated for greater language access and legal defense for immigrants in the city–this still-quite-narrow selection of languages disproportionately affects African communities, made up of people from one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world. The challenge here is both in accounting for the multitude of languages and regional dialects spoken in these communities, but also facilitating access for those who, even in their native language, struggle with literacy.

The impact of not participating in services offered by the city is effectively an exclusion from resources that could greatly benefit working families, including assistance with things like filing taxes or help with securing home mortgages. Sometimes the exclusion feels less accidental. The inaugural African Diaspora Legislative Breakfast hosted by Express Connexion at The Africa Center in Harlem this month brought together community leaders and representatives from state and city government to discuss the legislative priorities of the African diaspora. State Senator Cordell Cleare of the city’s 30th district remarked on her yearslong, and ultimately unsuccessful, fight in Albany to keep operational the Lincoln correctional facility, the last remaining prison work release program in all of downstate New York, only to see it recently reproposed as “The Seneca,” a new residential development expected to offer units with monthly payments that come out to about $40,000 a year, in a city where black households earn an average of $53,000 per year. “We need to fight to ensure that the same institution intended to lock us up does not become the housing to lock us out.”

(Photo by: Rashawn Austin)

The sense of exclusion can be indirect as well, as community-based organizations working in these neighborhoods often find support for their work difficult to come by. Sabine Blaizin, Deputy Director at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute based in East Harlem, described feeling “pushed out” of grant funding opportunities in the city–the lifeblood of institutions like theirs–whenever they got unambiguous about the communities they serve. “There is some risk in naming who we are. Things that sound Africa-centered are sometimes much harder to get funded.” The whiplash of rapid gentrification through their neighborhood is compounded by a sense that organizations such as theirs, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in the community next year, are not being prioritized in efforts to preserve the city’s cultural vibrancy.

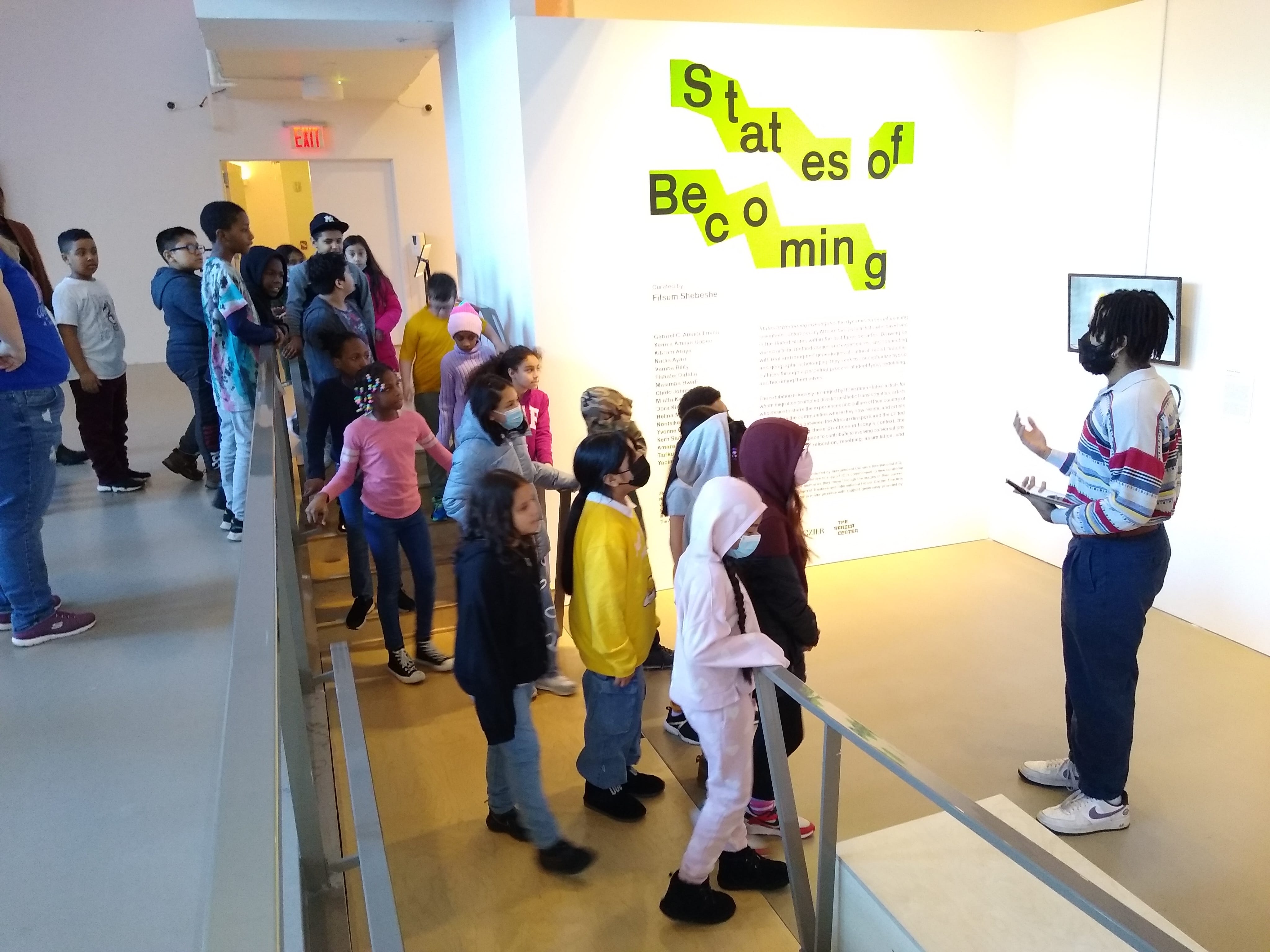

An array of museums, nonprofits, cultural institutions, and student organizations across the city develop regular public programming focused on the arts, history, and culture from the continent and its diaspora, but also designate their buildings as safe spaces, and hold Know Your Rights trainings to better familiarize members with important civic and legal protections that they’re entitled to as residents of this city. Organizations like the Sauti Yetu Center for African Women have long provided essential care to women who have fallen through the cracks of the city’s care systems, filling critical gaps in support against domestic and gender based violence, legal issues, and reproductive health. It would be difficult to overstate the importance that these organizations have had to the ability of African communities to persist in this city, or to argue against their being deserving of greater consideration in the allocation of its public resources.

(Photo by: Rashawn Austin)

Reforming the criminal justice system in New York City has been thoroughly examined, including the impact these systems have on the lives of vulnerable youth. For some African kids in the city, these risks are amplified by how destabilizing the transition to life in a new society can often be on families. “The migration process has shifted the ways we grow up,” according to Christelle Onwu, CEO & Founder of Express Connexion, who previously served as the inaugural Advisor for African Diaspora Communities with the New York City Commission on Human Rights for over seven years under the Bill de Blasio and Eric Adams’ administrations. The realities of economic life here can have a particularly unsettling effect on established dynamics within the family unit and upset the structure in a young person’s development. At a critical time in their lives, these kids run an increased risk of falling off track academically (or worse) as they navigate a city where one's immigration status can raise the stakes of even minor encounters with law enforcement.

As we try to conceive of ways forward, we can be encouraged by the fact that much of the important work is already being done. Advancing the interests of African communities in this city will likely require a combination of the continued efforts of the individuals and organizations working in government and in these neighborhoods everyday to make this city accessible to all who choose to live here, as well as the effective leveraging of the collective community’s political strength in numbers. African communities are a growing part of the city’s total composition, and as the city’s African population increases so too will the need for these communities to be adequately represented in city affairs. The fundamental task for community leaders in this moment is to ensure that this political capital can be translated into actionable strategies for people in these communities to live lives of dignity and continue to believe in the promise of this country.

(Photo by: Rashawn Austin)

The city’s mayor can be a critical part of this process. The efforts of these community advocates will ultimately only be as successful as our institutions allow them to be. They need a mayor who will be a partner–a mayor who understands that even within the larger African community there exists too much variation in the lived experiences and legislative priorities of smaller sub-regional, or country-based communities to rely too heavily on their overlapping qualities in trying to understand them individually. A mayor who seeks to understand the most pressing front-page issues but also sees alarm in the disproportionately high rates of divorce within African communities, the underreported incidences of gender-based violence, and the many harrowing experiences of children bundled through the city’s child welfare system.

Without the focused support of the city through sustained engagement and the effective direction of its resources to address the localized impacts of big-picture challenges, African communities will continue to find a city that feels like it no longer wants them here. Throughout their campaigns, the candidates have all expressed similarly high regard for the intricate tapestry of people and cultures that make this city exceptional. Stemming the exodus of working class people from New York City has emerged as a central focus of stump speeches, but what remains to be seen is the extent to which they each look to embrace the often confounding nature of this task, and how much they accept the complex but important responsibility put upon them to ensure that this city continues to reflect the important ideals that it has always represented.

Tunde Olatunji is the Associate Director of Policy at The Africa Center.