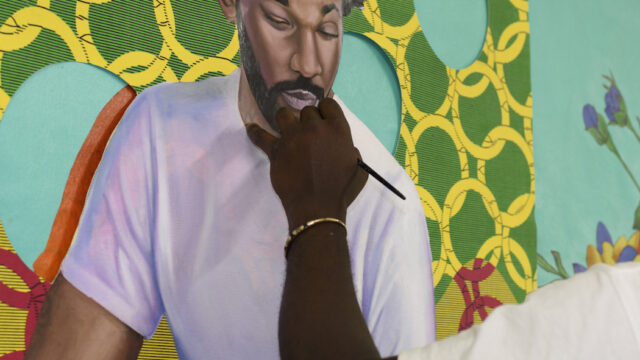

One on One with Patrick Quarm

Courtesy of the artist and albertz benda, NY

The Africa Center’s One on One interview series highlights the movers and shakers within the culture, business, and policy landscape of Africa and its Diaspora.

This One on One features artist, Patrick Quarm, who lives and works in Takoradi, Ghana. His first solo show in New York City, Patrick Quarm: SALVAGED IMPERIAL is currently on view at albertz benda gallery through October 3, 2020. The exhibition comprises a new body of work, ranging from intimate portraits to monumental tableaux, that establish a new visual language for expressing hybrid identities. Quarm graduated from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana, in 2012 with a BFA in Painting. In 2018 he earned a Masters of Fine Art from Texas Tech University.

Courtesy of the artist and albertz benda, NY “My task or my duty as an artist is to strip each layer after the other to bring clarity; to understand the past and how the past shapes the present.” – Patrick Quarm

Courtesy of the artist and albertz benda, NY “My task or my duty as an artist is to strip each layer after the other to bring clarity; to understand the past and how the past shapes the present.” – Patrick Quarm

Patrick Quarm: Salvaged Imperial at albertz benda is your first solo show in New York. How does that feel, and what does it mean for the development of your career?

It feels great! Being here was always a dream but now it has become a reality, and I’m thankful to albertz benda gallery for making this opportunity possible. Thinking back to graduating from my MFA program at Texas Tech University, I had no idea where my art career would take me. All I had was hope, remarkable paintings and hard work. My consistency brought great opportunities my way.

Having my first solo show in New York is exciting because it puts my work in a space where the right people will see it, and hopefully bring the next wave of opportunities. Hence, I will keep riding the wave and doing my best as they come.

Your work is an exploration of history and the duality of your and your protagonists’ identities; does it also make commentary on current social and/or political issues? If so, what issues does it address?

Yes, my work does make commentary on political issues. However, I do not approach these political narratives in my work directly. By taking a closer look at my work, the viewers’ experiences will prompt them to ask thought provoking questions as they navigate through its layers.

This to me is the first step in understanding who, why, and what identity means in the 21st century, and how it connects to all others including political dialogues. Narratives arising from the current political climate stem from conversations around universalism, transculturalism and the idea of cultural authenticity. In order to understand the Black experience, one must not view it from the present narrative but try to understand it by thinking through events of the past and how it has shaped the present. Erasing the body and deconstructing the body is a way that I am giving a glimpse into the system that has shaped the Black figure into a hybridized realm. In my work I approach such narratives by using layers, cutting and erasure.

My work is political in the sense that it allows us to view the two sides of the coin in relation to time: past and present events. The aim is not to present a solution or conclusion, but to initiate a conversation that allows us to understand the dual nature of history. My hope is for these questions to start a conversation and allow one to come to a stage or point of enlightenment.

Who are your biggest influences and where do you draw inspiration from?

My father has been the biggest influence in my life and practice. I always refer to him as a postcolonial gentleman. As a young man, I clearly recall him telling me “learn how to speak your own language before you commit to that of another man.” This is the kind of influence that shaped my thinking at a young age, promoting my quest to understand the hybrid individual and their existence in a given space.

From Frantz Fanon’s quote “In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself,” my inspiration is driven by life. Moving through cultural spaces in the world has allowed me to assimilate, adopt, and merge within cultures. Painting becomes a diary that I use to document, voice, and reflect on these experiences. With my own as a starting point, I aim to invite the viewer to reflect on their experience and connect with a broader definition of cultural hybridity.

You were educated both in Ghana and here in the U.S.; what kind of influence do you think this has had on your work and artistic practice? It would be great to hear your thoughts on this moment for the Diaspora. In what ways do you think art and culture have influenced it and will continue to serve it in the future?

Interestingly my undergraduate education in Ghana was still rooted in the Western education system. The educational system of painting was based on the Western style and the notion of it due to Ghana’s colonial past. This shaped my understanding of art not through the African lens but that of the West. Upon starting my MFA education in the USA there was the constant question of “why don’t you make African paintings?” I found these questions problematic for their narrow view of what comprises African art. It frames African art in a stereotypical way. Despite these issues, these questions took me on a journey of self-discovery and bridging the narratives between these spaces. Both cultures shaped my identity and my experience as an African artist living within a cultural third space. Embracing these two influences gave me a way to establish a unique language using materials, processes, and tools that embody the histories of both cultural spaces.

I believe that we are living in an interesting time. I always roll back the chapters of history, to that moment where the African artist made beautiful artworks, but the artist was never recognized and rather labeled “anonymous.” Today the creatives of the Diaspora get to cement their names in history—something for the current and next generation to look up to as an inspiration point. Art has always brought about the invention of culture, and the more the Diaspora continues navigating on building a universal language, evolution will never cease to exist. With that comes an endless possibility of a future that holds no boundaries.

Your new body of work has a three-dimensional aspect. How did this change come about? Does it represent anything and are you planning to continue working in this style?

The studio is my lab, and as an artist it’s where I constantly have my experimentations and play with ideas both personal or universal. The three-dimensional nature of my work came as a result of trying to find answers to my hybrid identity. I started thinking about history and its progression through past, present and future. I posed the question: what do I uncover when I flip the chapters of history? This prompted my interest in comparing and understanding history to how archeologists physically excavate a site in order to make meaning of events. Excavating by digging and cutting through layers of sedimented events paralleled my process of gluing layers, separating layers of materials, cutting, collaging, and erasing as a thoughtful process in the studio, allowing my works to embody the characteristics they do now.