Notes Toward a ‘Future Planning'

African Focused Community Development for New York City

By Diane Enobabor

“We must dare to invent the future"- Thomas Sankara

About a year ago, I founded (and ended) a rapid-response coalition of non-profit groups and mutual aid volunteers called BAMSA (Black and Arab Migrant Solidarity Alliance) to address the needs of continental African and Arab asylum seeking men after the opening of the Stockton Respite Center in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Black men, between the ages of 17-65 years old were forced to sleep in liminal prisons called unfinished shelters on congregate style cots above the concrete floors. The men did not have access to showers and were forced to go to the pools to bathe and the food situation was horrible, we had to fight to get access to halal options. That summer, Stockton Respite Center and Bushwick City Farms looked like a refugee camp in the middle of one of the most historically underserved communities in New York City. Initially the work was difficult and marginalized—doing mutual aid on behalf of African migrants did not resonate as important to other ethnic mutual aid groups and nonprofits. We fought to bring awareness and to challenge the Adams administration assertion that there was no more room in New York despite being a so-called ‘sanctuary city.’ As a daughter of Nigerian immigrants, seeing our men like this: vulnerable, shuffled in and out of temporary shelter, discriminated against because of language and scavenging for food and temporary work in New York was not only infuriating but also embarrassing.

One year later, things have not changed much for our community. Many mutual aid volunteers, experts on immigration and grassroots non-profit workers struggle to fill the needs of these men as well as women and children. Yet, despite the media attention from the spectacle at Roosevelt Hotel where African migrant men slept on cardboard mats and waited for days outside to receive an appointment to be placed in temporary shelter; and the historic City Hall’s hearing on the experience of Black migrants in New York where almost a thousand African asylum seekers and advocates mobilized to fight for justice, the majority of the community is still without comprehensive case management. This includes access to housing, education, legal representation, and work authorization.

Author's image from the Town Hall meeting. (Source: Diane Enobabor)

Immigration scholars and activists know that bipartisan politics make immigration reform indeterminable and new immigrants are usually left waiting for residency and eventually citizenship. Despite these limitations, historically migrants have been able to forge new communities and expose more room in the United States. If we are able to do this, is it really only up to Mayor Eric Adams to ensure a holistic and inclusive infrastructure best equipped to support new African newcomers to New York? If it is not, whose responsibility is it to support community development for African immigrants? And really, what do African communities need in the U.S. and how can we achieve this through future planning?

The Problem

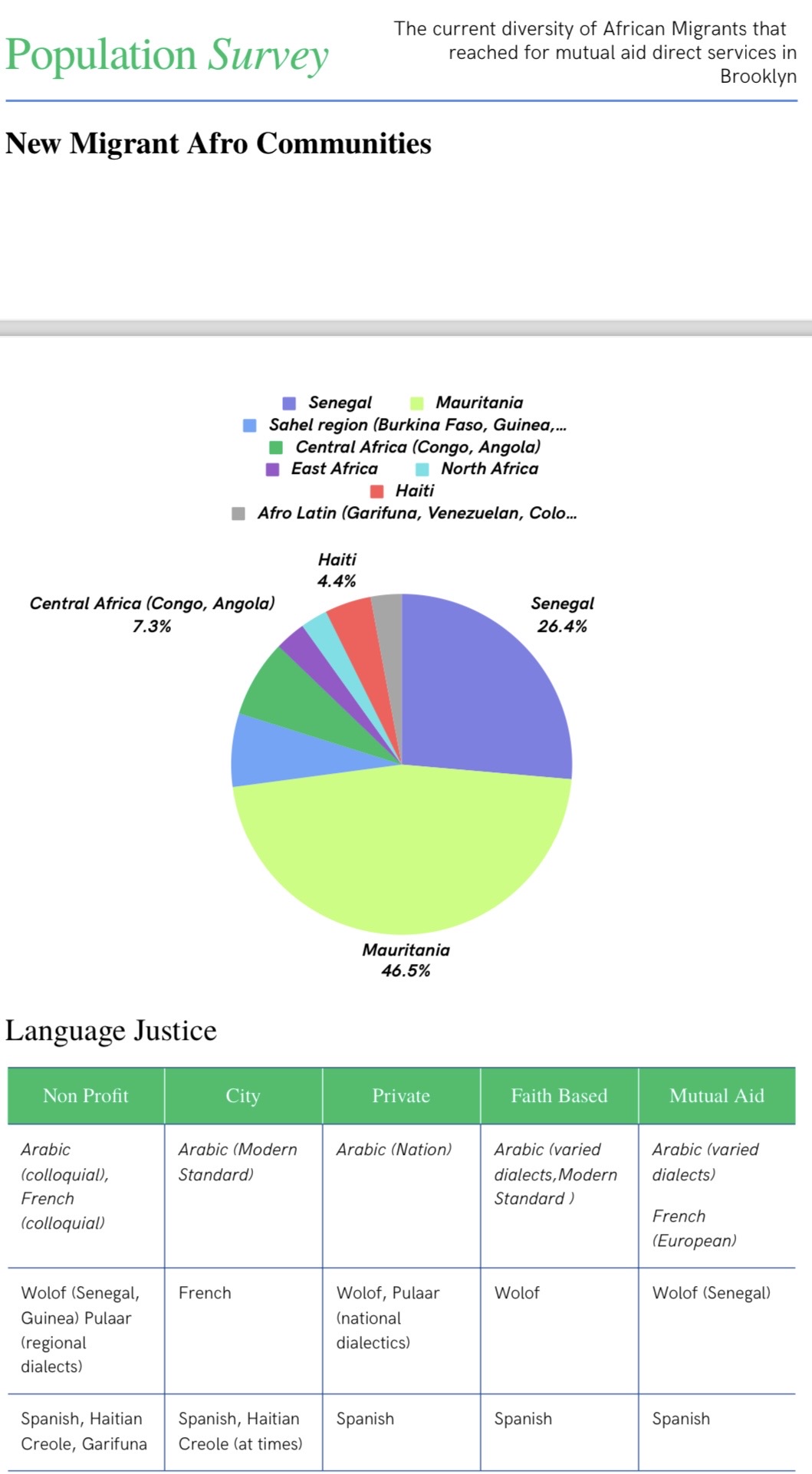

New York has received and documented over 180,000 new asylum-seeking newcomers. Although there has been acknowledged official irregularity in data collection on behalf of African continental asylum seeker newcomers to New York, the estimates that do exist demonstrate that one out of seven African continental migrants have entered the migrant shelter system. It is imperative to note that this may be larger as long-distance African migrants at times use documents from other countries in the Americas they may have had residency in before reaching the United States. Within this population, less than 20 percent of this population has been able to successfully apply for asylum in New York where there is less than five percent chance to be granted asylum.

African families, men, women and children were welcomed from buses at Port Authority in New York by community activists like Guinean-American Adama Bah, Founder and Executive Director of Afrikana or Power Mahu of Artists.Activists.Athletes. Those who arrived at the Port Authority on the bus were forcibly placed on them from states like Texas to sanctuary cities like New York after being processed by the Department of Homeland Security as asylum-seeking. Others may fly into JFK airport in NYC and are processed by DHS at the port of arrival. From the date of their processing, or at times release from immigrant detention, they have one year to file for asylum or alternative refugee statuses with the U.S. government. At asylum seeker arrival centers like the Roosevelt Hotel, new asylum seekers are 'triaged' for migrant-specific case management and placed into temporary housing. Our communities inability to secure permanent housing, work and access to social services is due to lack of case management in the African community, refusing access to IDNYC (identification card for New York City residents), lack of language accessibility for French, Arabic and indigenous African speaking migrants, discrimination in shelters including premature removal from respite centers, and anti-Black and African xenophobia at migrant assistance places.

(Source: Diane Enobabor)

Context (Federal)

Following the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, African immigrants typically arrived in the United States on student or work visas which put them on a pathway to permanent residency and citizenship. They were received by the United States as a calculated skilled labor force invited to fill labor and development needs in different regions of the United States. Following the work of sociologist Mamdi Corra, in his text, African Immigrants in the United States, we can trace this new wave of African newcomers outside of the skilled labor visa economy to the early part of the 1990s. By the early 2000s, a diversity of African migrants and their migratory status (undocumented migrants, economic migrant, worker, student, refugee, humanitarian) began to build new African communities all over the United States. By 2015, over 85 percent of continental African migrants had permanent residency.

The racist policies of the Trump administration formed the irregular migratory system African asylum seekers are navigating today. His “Muslim ban” and “shithole countries’” tirade laid a foundation for what’s happening now. With the COVID-19 pandemic pushing countries to the brink of economic and political crisis- African folks migrated en masse. In 2019, the Trump administration enacted what was called the Migrant Protection Protocols, otherwise known as “Remain in Mexico.” This practice of border externalization required asylum seekers to prove that they were unable to receive asylum in other countries they traversed through before reaching the border of the United States. In 2021, the Biden administration continued these militaristic and deadly border externalization procedures under what was renamed as the Title 42 Act.

Anti-Black racism also exists in the formation and implementation of immigration policy in the United States and the limits of mobility of Black migrants. The case studies on anti-Haitianism in U.S. foreign policy and immigration protocols are an eminent example. We cannot forget the Haitian migrant who was whipped by Border Patrol on horses attempting to cross the Rio Grande in Texas to bring food to his family. Advocates and social service providers trace the deliberate ignorance and lack of data collected on who is coming from the African continent in correlation to the federal government's inability to properly survey what nations should be considered for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or extended humanitarian visas. These limits force extreme journeys to the United States. Long-distance African migrants, traveling through Latin America and crossing the Darien Gap, whether solely through flight or a combination of flight, bus, and foot, can be trapped migrating on and off for years, spending upwards of $20,000 to travel (money raised by community efforts). They can end up trapped in detention centers in places like Tapachula, Mexico, or even in U.S. detention centers before being allowed to meet border patrol to be processed for asylum. Anticipated by AI surveillance tech scholars, the current face recognition program that operates the border control application that schedules appointments operates on anti-Black facial recognition bias. For every Black person from Latin America or Africa who receives a date weeks into the future, lighter skin migrants coming from Europe or Latin America may receive their scheduled appointment within a day or two at the border.

Context (Local)

Mayor Eric Adams is only as powerful as the constituents that have elected him to do so. Unfortunately, the majority of his constituents are not as educated on what strategies have been initiated in New York to assist asylum seekers despite its designation as a sanctuary city. In 2022, the Adams administration measured the influx of asylum seekers against the prior influx of federal funding to the city of New York for COVID-19 operationalized MOIA (Mayor's Office on Immigrant Affairs), Department of Homeless Services, NYC Health and Hospitals and and Office of Emergency Services to create a system to best address the needs Asylum seekers that were bussed from the U.S./Mexico Border. They rapidly expanded their capacity for shelter and case management by utilizing New York hotels and temporary makeshift tent shelters to host asylum seekers. African companies have not been contracted as vendors to support migrant infrastructures.

In 2023, at the end of Title 42, the surge of asylum seekers appeared to overwhelm federal and state administrations. RFPs (requests for proposals) and new department affiliations for the asylum-seeking crises formed a tiered shelter system that further marginalized Black African men from case management, legal support and access to work authorization. $500 million federal and state dollars were committed to caring for asylum seekers was paid out to private corporations like MedRite and DocGo with no actual case management provided by these companies. These security employees have been documented for physically and verbally assaulting African asylum seekers.

“The future belongs to those who prepare for it today”- African Proverb

Even with examples of other ethnic communities absorbing newcomers and further developing neighborhoods and communities in New York, African asylum seekers and African social organizations have not been able to do the same and retain newcomers while developing African businesses and institutions. For instance, communities like the Chinese in Flushing, Queens or Ukranians in Manhattan and New Jersey have been documented for receiving and successfully assimilating new asylum seekers from their communities into civic engagement, social services and employment. These communities have business leaders, real estate developers, migrant advocates and social workers prepared to organize and design new infrastructures within their neighborhoods for the shifting demographic of their community.

Case studies in other global major cities like Sao Paulo, Brazil, which has been celebrated as the largest, and most welcoming refugee-receiving city, has a municipal plan for migrants that highlights the potential needs of both continental African refugees and economic migrants a decade into the future. These examples allow us to imagine new futures where the U.S. can be an example for countries like France and the UK that fortify deadly border externalization policies in Tunisia and Rwanda.

The so-called "migrant crisis" is simply a result of mismanagement of migrant aid at the municipal, state and federal levels. Abolitionist and geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore's concept of "organized abandonment" may offer us a way to think through these bureaucratic limits. Under organized abandonment, we can trace the divestment in communities like New York City toward wasteful, unmitigated investment in the private sector. For example, the $500 million dollars lost to DocGo, a company that failed to deliver case management, could have been invested in public services for all New Yorkers including new migrants.

One solution to avoid this problem may be to recognize and invest in our people as the purpose and center of community development and planning. The concept of "people as infrastructure," coined by urbanist Abdou Maliq Simone, highlights how the social connections within working-class communities in Johannesburg can create expanded spaces for economic and cultural activities for residents with limited means. This is evident in how community spaces like African restaurants, markets, ethnic associations, sports clubs, banquet hall parties and religious institutions define African placemaking. Now celebrated African communities in Houston, PG County (Maryland), Columbus and Minneapolis, developed over time by people-focused advocacy as the community foundation and their needs were considered toward building the city's infrastructure. The local governments, in response, simply affirmed and supported what already exists based on the terms of the community.

African presence and action are imperative for us to see these types of communities exist in the future.

Policy Recommendations

Expand TPS to include sub-saharan African countries that are either at the lowest 10 countries indexed for insecurity or poverty index for Humanitarian Visas and extend TPS for Haiti. Also measure the eligibility for TPS as per country of origin instead of country of temporary residency as toward entering the United States. Currently, only six out of sixteen countries eligible for TPS are either on the continent or in the African diaspora. TPS ensures federal funding that is able to support the needs of new African asylum seekers in organizations that are able to provide case management. Historically, the United States has granted other types of humanitarian pathway visas to areas of severe conflict from refugees leaving Cambodia and Vietnam to as of recent Ukrainian and Russian asylum seekers under operation “Uniting for Ukraine”. Currently, the Haitian reunification program did alleviate pressures of Black migrants especially those that were stuck at the U.S/Mexico border. However, there are apparent limitations of ability to be able to schedule an appointment with CBP and the U.S. is ending the reunification program and deporting Black migrants. We must demand for humanitarian visas to be extended to Sudan, Congo, Tigray, and TPS for Mauritanians, Cameroonians, Haitians, and Liberia and case by case basis for Africans displaced by terrorism. We also must end Immigrant detention for all.

Start to organize and demand African vendors within city state and federal contracts with the orientation to actually develop African migrant neighborhoods in New York. Faith based institutions, including countless west African masjids provided housing with no city compensation. As of June 2024, there are no African vendors that are associated with the contracts employed by the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs in New York. Focusing on hiring African vendors would better assist with cultural competency- i.e. services for Halal food, translation and interpretation, and workforce training opportunities that best serves and develops new African migrant communities in New York. Also, expanding contracts to African vendors would overhaul traditional industries that assist with migrant inclusion but have historically excluded licensing Black migrants, in particular African women migrants. Some jobs sites include union construction labor, child care, food services, and rideshare companies- including taxi-coops.

Coordinate with the municipal government to assist with African service organizations to scale up to provide direct services and additional urban planning to stimulate African neighborhoods. ‘Little Senegal’ in Harlem, ‘Co-Op City’ in the Bronx, Crown Heights, Flatbush, and East New York in Brooklyn have African immigrant homeowners that have contributed to the development of these neighborhoods for over 30 years. It is time to see more than just homeownership but communities that we can expect to exist for generations to come that are welcoming to the same African newcomers that developed these neighborhoods. Organizations that provide direct services in New York like ABISA, ACT, Afrikana, Gambian Youth Organization, Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees,and others at a smaller scale not only offer immigration social services, but general guidance on how to navigate New York as Black and Migrant. Philanthropic initiatives from the diaspora of our professional class and actual state infrastructural surplus should go toward sustaining the work of these organizations not just as to meet the current political moment, but also in a way to best create a foundation and future for African migrants that are soon to come. We also need more trained African centered or conscious social workers, planners, lawyers, analysts, policymakers and real estate investors to be civically engaged and consult with local elected officials on the diversity and needs of African immigrants in New York.

Diane Enobabor, PhD Candidate at the Graduate Center, is the founder of Africa is Everywhere, a Pan African feminist grassroots initiative dedicated to welcoming and weaving continental and diasporic African migrant communities into their social fabrics.

Editor: Temi Ibirogba

This article is part of The Africa Center’s Policy Positions series, the recurring publications will offer thoughtful engagement with contemporary policy and governance issues related to the African continent. Policy Positions are submitted by members of The Africa Center’s community of thought leaders from across Africa and the African Diaspora. Follow @theafricacenter on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn to stay informed of new posts, and reach out to the editor to submit an idea for consideration.