Why Does Kenya's Music Industry Struggle?—and How to Fix It

By Naila Aroni

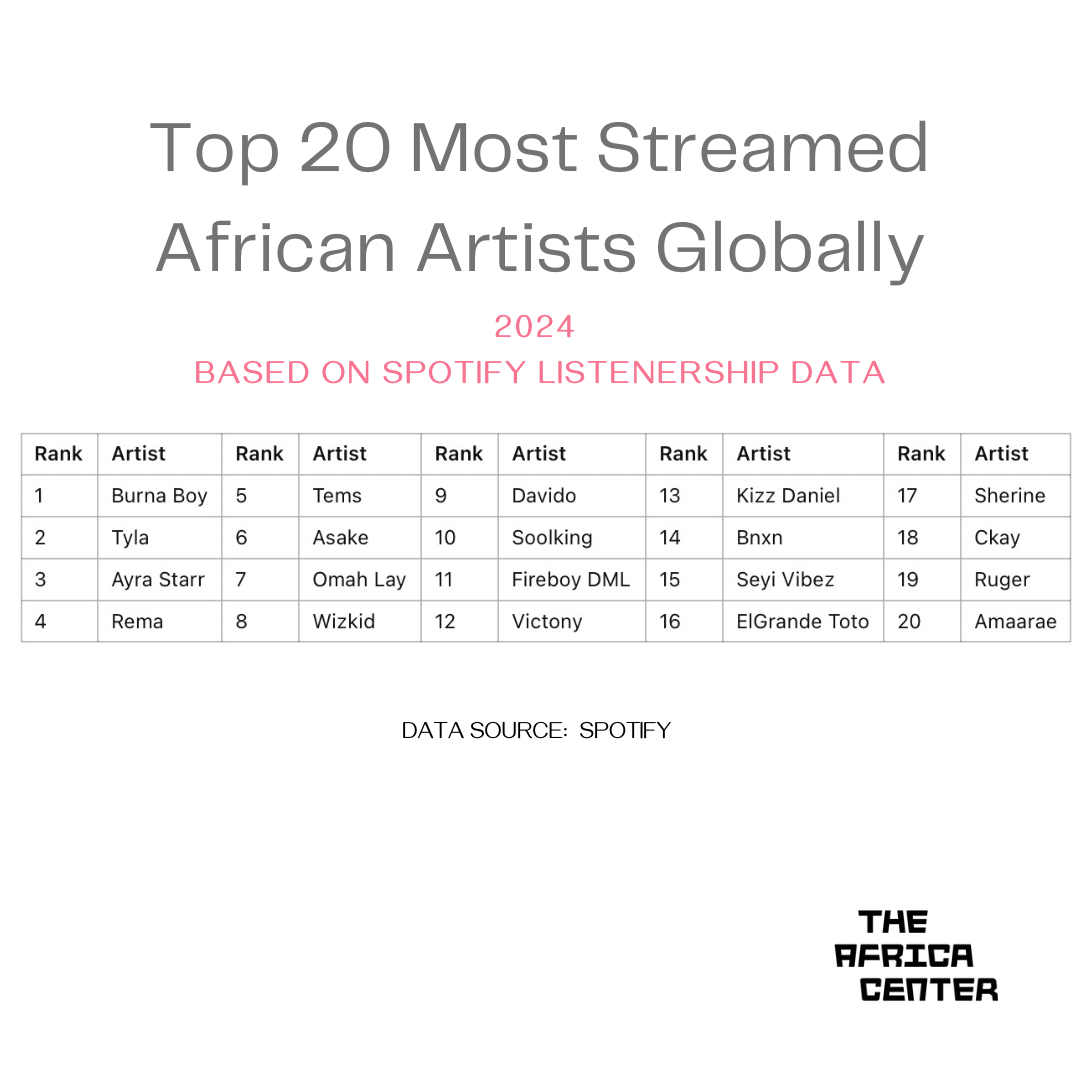

Despite Kenya’s rich cultural heritage, its music industry trails far behind creative powerhouses like Nigeria and South Africa, leaving Kenyan artists unable to fully reap the benefits of their talents. To paint the picture, local airwaves are dominated by non-Kenyan genres such as Afrobeats, Bongo Flava and Reggae. Streaming data also reflects a stark reality: only fourteen Kenyan songs were featured on Apple Music’s top 100 most-streamed songs within the country.

Mainstream narratives often claim that “Kenyan music has no identity” suggesting uniqueness is the currency Kenyan music is missing to achieve the global appeal of recognizable genres like Afrobeats and Amapiano. While Kenya can undoubtedly draw valuable lessons from its counterparts, particularly the importance of government support and private investment, simply replicating the South African or Nigerian models is neither practical nor advisable.

Both countries continue to grapple with issues such as widespread piracy and limited arts education. Moreover, despite Nigerian and South African music’s global success, the export-driven nature of their music industries has also not translated into substantial local economic benefits, failing to foster job creation or infrastructure development at home. Additionally social factors, like Nigeria’s large population and expansive diaspora, which played a significant role in exporting Afrobeats globally, give it advantages Kenya cannot replicate.

Instead, Kenya should aim to build a music industry tailored to its unique strengths, prioritizing local artists and audiences while fostering sustainable growth through robust infrastructure and regulation investment. Kenya’s distinct advantages include 1) diverse musical genres like Afrofusion, which blend global influences appealing to mass audiences 2) linguistic diversity which offers the potential for multilingual music distribution and 3) a growing creative economy. By addressing structural weaknesses and capitalizing on these strengths, Kenya can reposition itself as a leading music hub in East Africa, much like it was in the 1970s.

THE HISTORICAL ROOTS OF KENYA'S MUSIC INDUSTRY CHALLENGES

Colonial Rule

Unlike Nigeria and South Africa, where music became a cornerstone of nation-building after independence, Kenya's colonial legacy weakened its music industry's foundation. The suppression of traditional music, coupled with an education system that deprioritized the arts, created long-standing challenges such as limited arts education and a lack of government support, which are obstacles that persist today.

Before colonial rule, music was deeply embedded in Kenyan culture, serving as a means of storytelling, identity and communal expression through ceremonies such as weddings, funerals and initiations. However, under British rule, this cultural role was systematically eroded. Traditional music was censored to curb political dissent, and indigenous instruments were increasingly replaced by Western alternatives, disrupting the progression of traditional sounds.

Additionally, the colonial education system prioritized subjects like English and Mathematics instead of the arts. The goal was not to nurture well-rounded, skilled individuals but solely to produce a labor force for the colonial administration. Music was relegated to basic singing, with no structured arts education. Even after independence, between 1963 and 1978, there were no significant reforms to integrate music into the curriculum beyond music and drama festivals. It wasn’t until the 1980s that music was finally introduced as an elective subject, further stunting the development of a thriving music industry.

Post-Independence: 1960s and 70s

Despite these challenges, the 1960s and 70s marked a golden era for Kenyan music. This period saw a flourishing industry that significantly contributed to regional economic and cultural growth. Benga, an indigenous genre originating from the Luo community, gained immense popularity, influencing pop music across West and Southern Africa. Nairobi emerged as a recording hub, attracting artists from Tanzania and Congo, fostering cross-cultural collaborations that enriched the East African sound. Genres such as Lingala from Congo and Taarab from Kenya’s coast thrived, while major international record labels like EMI, CBS International and Polygram, alongside independent African labels, set up operations in Kenya, creating a vibrant and promising industry.

However, political interference and lack of government support curtailed this momentum. Under President Daniel Arap Moi’s regime, strict censorship policies suppressed artistic freedom. Benga and other non-Swahili genres were censored to suppress ethnic nationalism. Moreover, innovation and freedom of expression was stifled, as artists were pressured to produce pro-government or religious songs. This left Kenyan genres struggling to compete with imported music from other African countries.

The “final blow” to the Kenyan music industry’s growth, was compounded by rampant piracy and ineffective regulation. By the mid-1980s, piracy surged as cheap, pirated cassettes flooded the market, with corrupt law enforcers colluding with pirate cartels. Kenyan music was widely sold in markets like Nigeria, but local artists rarely received compensation. This led to the exit of international record companies from Kenya and the closure of many local labels.

Even though both Nigeria and South Africa’s music industries were also stifled by colonialism, their national governments made a greater effort to invest in the arts during post-independence, recognising the role of music in shaping nation building. In Nigeria, the government aimed to transform the oil money brought about by the oil boom into national identity. This included spending hundreds of millions of dollars organising FESTAC 77, (the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) which boosted Nigeria’s global position as a hub for the arts. Moreover, the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) was established and Nigerian radio stations were mandated to play a significant percentage of local music.

Guards from Bornu in Kaduna State during FESTAC ‘77 (January 15 - February 12) (Source: Helinä Rautavaara)

HARNESSING THE KENYAN MUSIC INDUSTRY'S STRENGTHS

Kenya’s music industry possesses unique strengths that, if properly harnessed, could drive both local and international success. As previously mentioned, one of these strengths is its diverse musical identity. An excellent case study of how diverse genres like Kenyan Afro-fusion can succeed both locally and internationally is Sauti Sol, Kenya’s most globally recognized musical act. Their sound incorporates influences from Benga, Lingala, African Rumba, Mande music, pop, and R&B, creating a dynamic and rich musical identity. Additionally, their multilingual approach, singing in languages such as Swahili, Luo, Luhya, English, to name a few, has broadened their reach across East Africa, particularly in Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Swahili is widely spoken. These factors have contributed to Sauti Sol’s longevity and relevance in the region’s cultural landscape for over a decade.

Sauti Sol, the Afro-Pop group from Kenya, comprising of Polycarp Otieno, Savara Mudigi, Bien-Aime Mudigi and Willis Austin Chimano (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Beyond its musical diversity, Kenya’s strategic location as East Africa’s economic hub positions it as a natural center for music production and distribution, much like it was in the 1970s. This business-friendly environment has led to renewed interest from global players like Universal Music Group, which has partnered with local firms to promote Kenyan artists internationally. Additionally, Kenya’s vibrant festival scene, featuring events like Blankets and Wine and Oktoberfest, makes it an attractive destination for touring musicians, further integrating the country into the global music network.

Kenya’s growing creative economy also provides a strong foundation for industry expansion. The creative sector already contributes 5.3% to Kenya’s GDP and employs over 250,000 people. With a youthful population and an expanding middle class, disposable income for entertainment and music consumption is set to rise, mirroring how Nigeria’s oil boom in the 1970s fueled record sales and contributed to the growth of its music industry. However, for Kenya to fully capitalize on these strengths, significant government investment is necessary.

DIGITALS RIGHTS AND DATA PROTECTION

Moreover, there is a greater need for effective regulation to address digital rights and data protection. Kenya’s Copyright Act (2001) is outdated and fails to address current challenges in the music industry in line with technological advancements. “The process of royalty collection and distribution right now simply does not work, because it’s outdated, especially in light of technological advancements”, says Selina Onyando, Kenyan artist and Creative Industries Policy Consultant. The existing law doesn't adequately address how royalties are calculated and distributed from streaming services, leaving artists with low earnings from platforms. Moreover, the act is silent on data ownership and privacy which leaves artists vulnerable to exploitation through the misuse of their data on distribution channels or losing out on potential income streams.

Although the Copyright Act outlines penalties for copyright infringement, enforcement of copyright infringement remains weak, sustaining high piracy levels. With three Collective Management Organizations (CMOs) in Kenya, there's duplication of roles, and the sector is marred by allegations of corruption and mismanagement. Despite being one of Africa’s top three revenue-generating CMOs, the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK) ranks among the lowest in royalty payouts. It is estimated that MCSK could collect over KShs. 110 million in unpaid royalties from broadcasters, yet it has faced multiple license suspensions due to corruption and mismanagement. Therefore, stricter oversight of Collective Management Organizations (CMOs) by the Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) is essential, ensuring fair practices and timely royalty payments. Limiting the number of licensed CMOs would improve resource allocation.

While piracy and copyright challenges persist across Africa, South Africa’s regulatory framework is more robust than Kenya. Unlike Kenya’s fragmented CMO structure, South Africa has a more streamlined system, with key CMOs specializing in specific rights: for performing rights, mechanical rights and sound recording respectively. This reduces overlap and confusion, ensuring that rights holders receive accurate and timely royalties. Moreover, CMOs like SAMPRA (South African Music Performance Rights Association) have secured reciprocal agreements with major international CMOs, facilitating global royalty collections for South African artists. Hence, this well-regulated system has positioned South Africa as the continental leader in royalty collection, which Kenya could also learn from.

CRAFTING OUR OWN PATH

South Africa and Nigeria’s global success isn't because their music is inherently “better” than Kenya’s. It’s due to stronger ecosystems that support their artists in ways Kenya has not. Additionally musical quality is subjective, shaped by personal taste and cultural context. Therefore Kenya can learn lessons from Nigeria, South Africa and even Korea’s music industries to capitalize on its potential. Moreover, Kenyan music’s lack of a distinct sound could even become a strength, allowing it to leverage its cultural diversity and reposition itself as a recording hub in East Africa, as it was in the 1970s. In other words: the talent and creativity in Kenya is undeniable. What Kenya needs now is infrastructure, investment and strategic vision to empower its artists and industry.

Naila Aroni is a recurring author at The Africa Center and an artist, writer and cultural analyst from Nairobi, Kenya. Her background in policy further informs her work, advocating for inclusivity and the sustainable development of Africa's creative economy.

Editor: Temi Ibirogba

This article is part of The Africa Center’s Third Spaces series, the recurring publications will offer social commentary and cultural analysis on topics pertaining to Africa and its Diaspora with the goal of addressing gaps in discourse. Third Spaces are submitted by members of The Africa Center’s community of thought leaders from across Africa and the African Diaspora. Follow @theafricacenter on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn to stay informed of new posts, and reach out to the editor to submit an idea for consideration.