Nigeria Online - Capitalism & Feminism

How Capitalist Individualism is Limiting Liberatory Discourse Among Women in the Nigerian Online Space

By Immaculata Abba

Unlike in the earlier part of the last decade, digital organizing and activism among online Nigerian feminists in the past few years has taken a lethargic turn. What is gaining popularity—across Nigerian online spaces, and not necessarily in the same spaces or among the same people who contributed to the digital activism of the past decade—is the idea of a ‘soft life.’ The rising popularity of a Nigerian ‘soft life’—reminiscent of the Western ‘girlboss’ in its capitalist individualism—within the Nigerian online space is one major way I see our attention and energies being co-opted to focus instead on the consumerist enjoyment and for-private-profit hustle. Enjoyment is a good thing and hustling is the only means to survival that most Nigerians have—and see—in the country today. However, given the collective potential that past digital feminist movements have shown us that we possess, if we invest in using the online space to increase our consciousness of the oppressive systems that govern us (and our roles/positions in those systems) and how we can remake the systems for our collective welfare, we can make tremendous gains in our conversations, policies and actions online and offline.

The 2010s produced a plethora of powerful online hashtag movements in Nigeria that catalyzed events, political action and even behavioral changes offline. To name a few key ones: In 2014, the #BringBackOurGirls campaign commanded global attention to the plight of schoolgirls abducted in Chibok by Boko Haram. In 2015, Nigerian women on Twitter convened over the hashtag #BeingFemaleinNigeria to share their experiences and critiques of patriarchal oppression. In 2018, #MarketMarch2018, organised by the designer and artist Dami Onosowobo, under the handle @MarketMarch, brought women around Lagos together to protest the normalised sexual harassment and bullying of women in markets. In 2019, Northern Nigerian women and church-going women used #arewametoo and #churchtoo respectively to out their abusers and articulate the state’s ineffectiveness in redressing violence. 2020 brought #MenAreTrash and the organizing of the Feminist Coalition who created a nationwide system of raising and disbursing funds and legal aid during the #ENDSARS movement.

Analysing the #arewametoo and #churchtoo movements in her 2020 sociology dissertation, daughters of disobedience: how nigerian feminists are using twitter as a tool for storytelling, resistance, and solidarity, the poet and playwright Lanaire Aderemi argued that these two key 2019 movements challenged cultures of shame and silence produced by patriarchal oppression while strengthening solidarity among Nigerian women across cultures and locales. As Nanjala Nyabola, author of Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics, puts it in the book, “Twitter is like a large in-ear translator: it allows the powerful and the disempowered to communicate to each other, to articulate their concerns via a mutually intelligible language (technology).” The same can be said of all other social media platforms.

However, the internet’s capacity for facilitating dialogue between the disempowered and the powerful is being severely underutilized in Nigeria’s case. Since 2020, the offline protest landscape across Nigeria has grown more effervescent as hardships intensify and where protests do not feel sufficient, Nigerians are looting and taking up arms. Yet, this offline proliferation has not been mirrored online. After all, only 7% of Nigerians are active social media users. Using a thematic and intersectional analysis of 700 #BeingFemaleinNigeria tweets from 2015, the researcher of class-privileged Nigerian women, Simidele Dosekun discovered that the predominant representation in those tweets were of the voice, experiences and concerns of “educated, capacious and confident urban career women belonging to the country’s higher socio-economic strata.” The movement, she found, was limited by its “lack of intersectional consciousness: the predominant story of the campaign was unrepresentative of the problems and experiences of the vast majority of Nigerian women.” As a Nigerian Twitter netizen myself, I have felt a sense of lethargy for digital political action after the 2020 #ENDSARS movement, with the 2023 elections being a brief exception. Granted, this may be as a result of the bias of what part of Twitter I live in. But it is undeniable that the Nigerian Twitter feminism landscape is not as ‘bubbling’ with activism or discursive resistance as it was between 2014 and 2020, or as it is offline.

For the Nigerian digital community, I suspect that capitalism is incorporating and choking us.

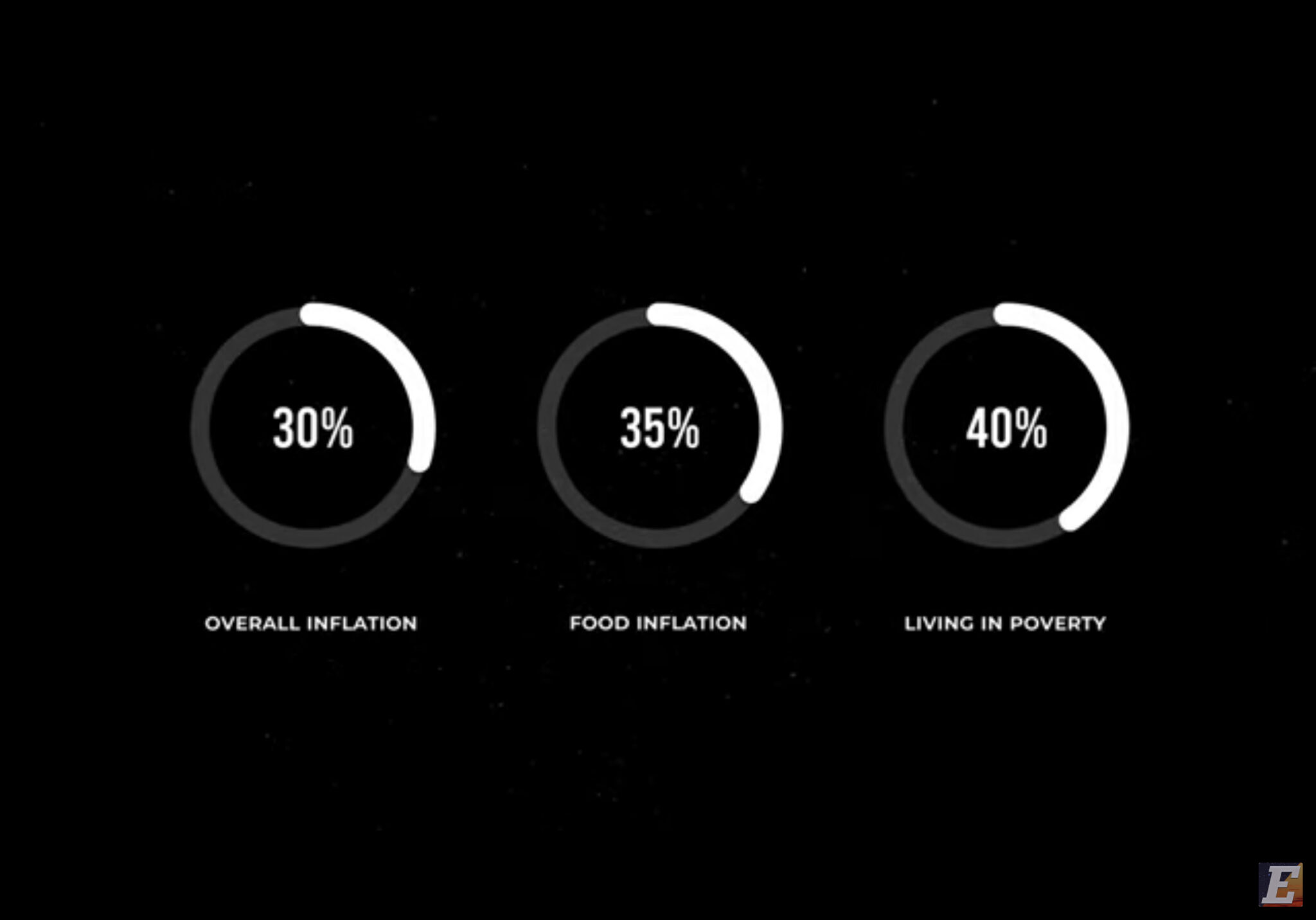

NIGERIA UNDER GLOBAL CAPITALISM

Nigeria’s current economic system is the product of its past and its current position in the global economy that is dominated by hyper-capitalism. As I have argued elsewhere, historically, Africa’s relationship with global capitalism has impoverished the continent and strengthened the unequal distribution of wealth in the world. In effect, we can hold capitalism responsible alongside a mix of factors including legacies of colonial and military rule, corruption in public offices, an oil-dependent/undiversified economy and persistent insecurity. One finds that the world’s issues all have shares in each other, a vicious cycle where the sustenance of one is the sustenance of all: capitalism’s insatiable demands have resulted in the exploitation and unequal distribution of resources which incites conflict and persistent insecurity weakens a country/region’s economic capacity, thereby leaving it more susceptible to exploitation. For the sake of this article, let us focus on capitalism’s role, especially because of how it shapes both Nigerian women’s aspirations and what options are available to them to pursue and reimagine those aspirations. Due to the problem factors in the paragraph above, Nigeria’s food inflation rate jumped above 35 per cent at the start of the year, the cost of living here has reached levels not seen since the mid-1990s, the Naira has been slumping to record lows for months, and with our import-dependent economy, the prices of medicines, transport, overhead business costs, production materials are rising daily.

(Source: Economist Explains)

#GIRLBOSS VS #SOFTLIFE VS A ROBUST THIRD THING

In the face of all this hardship, it is no surprise then that, instead of the hustle-laden idea of ‘girlboss’, the ultimate aspiration in the current Nigerian youth imaginary is a ‘soft life.’ The rise and decline of the ‘girlboss’ movement has been highly documented in the Western world but less has been written about it from the perspective of an African woman. There is no general consensus on Nigerian ‘girlboss’ icons the way you think of American girlbosses and images of Sophia Amoruso or Sheryl Sandberg flash through your mind. But there are some aspirational figures in the same vein across various Nigerian imaginaries: the likes of Ngozi Okonjo Iweala (a name synonymous with The World Bank here), Funke Akindele (director of the first Nollywood movie to surpass N1 billion at the box office), Fisayo Longe(Forbes 30u30 honoree whose fashion brand, Kai Collective, has amassed a global cult following online). The same ‘girlboss’ characteristics apply: high public profile, association to financial capital in a way that screams ‘unbelievably liquid’, career-driven and an aura of #slay.

That being said, the term ‘girlboss’ hasn’t migrated verbatim from the USA-UK Western world axis to Nigeria culture because the socio-economic landscapes are totally different. Today in Western media, to be a ‘girlboss’ is not cute. On TikTok, with phrases like “Gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss”, Gen Z now pokes fun at clueless millennials who once uncritically bought into the notion that craven careerism is somehow inherently empowering. Isabel Slone at Early magazine argued that for the ‘girlboss’, feminism was a brand building exercise rather than a show of solidarity. Amanda Mull at The Atlantic declared that ’The Girl Boss Has Left the Building.’

And yet, as a term used to describe “a self-made woman, running their own business, and acting as their own boss”, the ‘girlboss’ remains not only a common aspiration for many Nigerian women, but also the default. In Nigeria, most working women, like their male counterparts, run their own businesses. According to Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics, in Q2 2023, 91% of employed women in Nigeria were self-employed. But this self-employment is not glamourous, according to the ILO, nearly all Nigerian self-employed women are in informal, thus precarious, employment.

The term ‘soft life’ is currently in that early conceptual phase where meaning is being negotiated around ideas of financial stability, social status and luxury around ideas of financial stability, social status and luxury.

In one interpretation, the Nigerian digital magazine Zikoko, which draws the origin of the ubiquitous online slang to the digital Nigerian community, writes about financial stability and progress: “Soft life is slang for living a life of comfort and zero stress — one where sapa [the state of being broke] and village people [aka ‘enemies of one’s progress’] don’t exist.”

Another interpretation is of social status and its signifiers in the form of the marriage-kids-job trifecta, as articulated by Twitter user @Ewa_oyin. In response to the question “Where do you see yourself in 5 years?” she replies “Married, rich, a spoilt wife with twins and a lil boy, one of the top businesswomen in Nigeria.” Not just any marriage, but marriage to a rich man; not just any children, ‘twins and a boy’ to signal fertility and because Nigeria is a patrilineal society; not just any job, not just any form of employment but self-employed as ‘one of the top business women in Nigeria.’

A third meaning of ‘soft life’ is the luxury of travel, foreign associations and exclusivity. This version is iconically captured in Koromone Koroye’s spoken word single ‘Soft Life Manifestations’ (the opening for Ajebutter’s 2023 album ‘Soundtrack to the Good Life’): ‘let’s begin in first class / breakfast is something light and French / foreign men with accents that make you blush / the girls that get it, get it / we don’t bark, we don’t bite, we don’t fuss, we don’t fight.’

And I get the allure of it. Nonetheless, Nonetheless, “[a] consumption-driven life is a fragile approach to securing social justice,” as researcher Désọ́lá Ọlálẹ́yẹ astutely argued in her essay on the pitfalls of current conceptualisations of a ‘soft life’ in the Nigerian imaginary. She suggested instead that: “Real softness may find us through a radical reimagination of care. We may encounter it through a stronger awareness of the fact that the route to a life of ubiquitous tenderness is more easily and safely traveled through a collective stride.”

Policy Recommendations

Everyday Attention to Power and Imagination Beyond Incorporation: In Feminism Interrupted: Disrupting Power, Lola Olufemi argues that imagination is the most powerful tool that feminists have at our disposal as it allows us to expand our sense of what individual and collective freedoms are possible for us beyond what is being offered by or immediately apparent in our current social and economic systems/realities. A March 21, 2024 tweet by @FeministsKE offers an example of what this alternative of radical imagination can look like in everyday practice.

“We must remain attentive to how power operates within self – how we are socialized to self-censor, to engage in self-surveillance, to police, not only ourselves, but others; to diminish our voices and ideas[…] Recognise the everydayness of this power, how it shows up in daily interactions, how we sustain it and how we can unlearn it.”

Investment in Media and Social Science/Humanities Research Projects: Investment in media and research in the social sciences and humanities: Besides individual efforts, governments and organizations can support collectively beneficial radical imagination and practice by investing in media and research projects that probe into power relations and dynamics in our societies and show alternative narratives where our radical imaginations are possible and how we can achieve them.

Advocacy for the Protection of Online Speech Rights: Since 2019, the Nigerian Senate has been debating different bills to regulate social media use in the country. Their primary argument has been that a law is needed to curtail hate speech, for the protection of the Nigerian state and its citizens. About the 2019 ‘Protection from Internet Falsehood and Manipulations Bill’, the Nigeria Chapter of the Internet Society warned that the bill contained overbroad provisions that could be easily abused to limit online expression of political views. Online petitions as well as international and local civil society organizations such as Amnesty International and the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) have been pushing back on the bills to protect citizens from state-surveillance mechanisms that either seek to–or, inadvertently–stifle freedom of speech. The recommendation here is for CSOs to continue with the advocacy efforts, with a focus on narrowing the provisions of these bills so that the outcome is a safer internet for public reflection and dialogue.

Immaculata Abba is a researcher and artist based in Enugu, Nigeria. Her current interests are in the Nigerian left, social healing and the power of the humanities.

Editor: Temi Ibirogba

This article is part of The Africa Center’s Policy Positions series, the recurring publications will offer thoughtful engagement with contemporary policy and governance issues related to the African continent. Policy Positions are submitted by members of The Africa Center’s community of thought leaders from across Africa and the African Diaspora. Follow @theafricacenter on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn to stay informed of new posts, and reach out to the editor to submit an idea for consideration.