The God of Money in Modern Nigeria: Wealth, Power and Morality

By Aisha Ayan

THE MAKING OF A WEALTH OBSSESSED NATION

There is little on this earth that money cannot buy. Throughout history, the pursuit of wealth has fuelled war, exploitation, inequality and the hardening of class divisions. In Nigeria, this has long found its roots entangled with colonialism. The British colonial rule not only imposed a capitalist framework that prioritised the economic gain of the empire, but also empowered a minority of local elites who collaborated for personal profit often at the expense of the wider society.

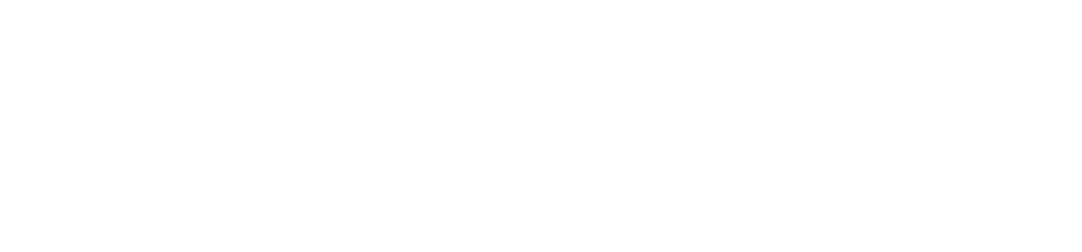

Since independence, the country has seen a steep moral decline, tied to greed and systemic corruption. The Abacha regime, a symbol of oil-era kleptocracy, is perhaps the most notorious example, with billions looted, institutions gutted and lives shattered under the weight of one man’s insatiable hunger for wealth. According to the International Centre for Asset Recovery, the Abacha family’s embezzlement is estimated at over $4 billion. But decades on the situation has not improved, if anything it has worsened with this corrosive mentality continuing. With this at the political background of society, the sound of prosperity gospel can not be muted. The level of wealth accumulation by mega churches, repackaged as evidence of God's divine favour is hard to ignore in a nation split between the haves and have nots.

THE GENESIS OF WEALTH WORSHIP: COLONIALISM, OIL AND GREED

In today’s Nigeria, wealth is everything. To be poor is to be invisible, even expendable. The obsession with wealth and by extension, status has contributed to a degradation of moral values and a complete societal decadence. What has emerged is a society where the rich are worshipped, no matter the source of their wealth, and social values are distorted beyond recognition. Ironically, the same nation which surpassed India as the world’s poverty capital in 2018, though it has since lost its crown, now has 87 million people living below the poverty line according to the World Bank and has developed an almost religious veneration of wealth.

To understand the present, one must trace the past. Nigeria’s wealth hierarchy and exploitative capitalist attitudes stem from its colonial legacy, which privileged extractive institutions and created a class of native elites to facilitate imperial economic interests. However, the postcolonial period did very little to dismantle these structures, in fact it bore a rather scary cancer instead. The first republics and military regimes bolstered a patron-client economy that persists today, where access to wealth is predicated on loyalty, cronyism and nepotism amongst those in power.

(Source: National Library of Nigeria)

The discovery of oil and the boom in the 1970s can arguably be seen as the genesis of Nigeria’s problems, the systemic inequality and today’s corruption. During this time, petrodollars were funnelled into the hands of a few while basic infrastructure and public services deteriorated. The Niger Delta region was pillaged and destroyed with little regard for the environment or the people living there, so long as billions were being extracted, nothing else mattered. Nonetheless, what is clear is that success was not based on merit but relationships and access to power—this is how contracts were awarded. Political appointments became opportunities for looting and the state evolved into a marketplace for patronage. This system created Nigeria’s current socio-economic and political template, which is the reverence of wealth above all.

MAKING WEALTH A DIVINE BLESSING: PROSPERITY GOSPEL PREACHING AND MEGA CHURCHES

When discussing the nature of wealth worship in Nigeria and the overwhelming emphasis on its acquisition, it’s impossible to ignore the impact of prosperity gospel. The rise of Pentecostalism in the 1990s coincided with the decline of the welfare state and rising unemployment, which left many citizens economically vulnerable. Many churches responded to this by promoting prosperity gospel to their congregation, which is a theology that equates material wealth and divine favour as ordained by God. Sermons increasingly focused their prayers on financial breakthrough, upward mobility and social status. Through this, the church positioned wealth as one of life’s most important and aspirational achievements.

Mega churches, undeniably, are architectural and symbolic embodiments of decadence and Nigeria’s declining morality. Pastors and religious leaders have become celebrities and demigods: flying private jets, living in opulence and accumulating wealth, while large swathes of their congregations continue to live below the poverty line. Yet these same congregants continue to “sow seeds” of faith, tithing with the hope that they too might be blessed with wealth.

Few artists have diagnosed Nigeria’s moral decline as clearly as Fela Kuti. In Shuffering and Shmiling, he candidly critiques Nigerians numbed by religious dogma, enduring hardship with blind hope as churches and mosques offer empty promises while exploiting them.

“Suffer, suffer for world Enjoy for Heaven Christians go dey yab "In Spiritum Heavinus" Muslims go dey call "Allahu Akbar"

Open you eye everywhere Archbishop na miliki Pope na enjoyment Imam na gbaladun”

His critique of religion in 1978 still speaks so strongly to today’s Nigeria, where suffering is ritualised and resistance is rare. Religious leaders are far from moral custodians and contribute to the moral decline. They offer empty hope and subvert scriptures whilst deepening their own pockets.

The ethics of mega churches need not be explained in depth. They operate through the exploitation of faith, preying on a flawed system that has failed its people and has created vulnerable minds who see religion as a way out or their only semblance of hope for a better life. The result of prosperity preaching has been the significant commodification of religion as arguably one of the most profitable businesses in Nigeria, with mega church pastors such as Bishop David Oyedepo, with an estimated net worth of $150 million. More so, it has stripped religion from its communal, altruistic ethos to a hyper-individualistic practice that sanctifies selfish ambition and material gain. The modern day Nigerian prayer is to be wealthy. The theology of prosperity gospel normalises greed and excess. It provides moral cover for wealth accumulation and discourages critical discourse of the system. Within the prosperity gospel economy, the ends justify the means and those who succeed are seen as inherently blessed (regardless of how they acquired their wealth) while those who suffer are urged to pray harder.

Winners Chapel Church in Okene, Kogi State. (Photo by Ayokanmi Oyeyemi)

It therefore would not be an exaggeration to assert that in Nigeria, money can purchase nearly anything. Wealth is revered. Why? Because it serves as one of the few reliable safeguards against the harsh socio-economic precarity that defines daily life for the majority. In 2022, the Multidimensional Poverty Index survey revealed that: 63% of persons living within Nigeria are multidimensionally poor, meaning that their poverty goes beyond just a lack of income, but covers various areas of deprivation such as education and health care. Hence, wealth functions as an insulator, shielding people from the dysfunctions of an unequal and unstable system. It offers dignity, respect and power. To be wealthy in Nigeria is not only to be protected from hardship and elevated from it, but also to inhabit a realm of privilege that often enables impunity. To be wealthy is to possess power, and in Nigeria, power often operates without restraint.

This creates a god like status, where the wealthy live by a different set of rules. They are exempt from the shared frustrations and inconveniences of everyday Nigeria life. They skip queues at banks, flout traffic laws with egregious convoys, evade legal accountability and in many cases, obstruct others’ access to justice. Such a level of power entrenches a class hierarchy so visible and so normalised that it feels institutionalised and glorified in nature.

Young man in Lagos. (Photo by Biola Visuals)

It is therefore unsurprising that for those who have borne the brunt of Nigeria’s systemic failures, this state of privileged ease becomes not just aspirational, but essential to any conception of a “good Nigerian life.” Yet this veneration of wealth is also a dangerous beast. Like all objects of worship, it demands a sacrifice. It has fuelled harmful and criminal pursuits of money. The rise of ritual killings, internet fraud (popularly known as “Yahoo Yahoo”), human trafficking and exploitative labour practices are all symptomatic of a society where material success is prized above all else, and the moral cost of attaining it is rarely questioned. This has resulted in a Nigeria where human worth is measured against the background of their wealth or proximity to wealth, and where those without it are disposable.

Suffering doesn't radicalise most Nigerians but it tends to motivate them to rise above others so they’ll never suffer again. In a society where the state has failed to provide even the most basic facets of human security: healthcare, safety and dignity, suffering is not interpreted as a collective failure demanding collective action, but rather as a personal misfortune to be escaped by any means necessary. This has created a mentality where the ultimate goal is not to actually dismantle the structures of inequality, but to ascend them and become the one who is served, obeyed and feared, even if that means adopting the very systems and behaviours that once oppressed them. This is why many people, once they attain wealth, replicate the same violence of exclusion and indifference they once condemned because deep down, justice was never really the goal, what they wanted was proximity and access to wealth and power, not its redistribution.

They do not want to burn down the house, they want to own it, and perhaps bar the door behind them.

THE DIASPORA: DETTY DECEMBER

Interestingly, the absolute authority of wealth in Nigeria has rendered the country a site where those with financial means from the diaspora can expect to be courted, catered to and elevated in ways that would be inconceivable in their countries of residence. This dynamic is perhaps most visible during the annual phenomenon of Detty December, a festive migration marked by enjoyment, spectacle and excess. While celebrated, Detty December has become increasingly contentious due to the overwhelming influx of returnees, which brings Lagos to a near standstill, straining already fragile infrastructure.

More significantly, Detty December reveals a class divide. For many members of the diaspora, the period represents an opportunity to indulge in a level of luxury and deference that their dollars and pounds can command in Nigeria. The local economy, eager to capitalise on this seasonal surge, readily accommodates and glamorises this elite status for the diaspora.

Front view of new naira note. (Photo by Koutchika Lihouenou Gaspard)

Nigeria, for its part, provides a fertile terrain for this behaviour to thrive. Its cultural and economic structures that valorise wealth as the singular metric of worth, facilitating a service culture where being hailed and treated like royalty is the natural reward for financial power. In this ecosystem, we see wealth worship come to light and Detty December becomes less a celebration of homecoming and more an exhibition of financial dominance and class stratification.

AT THE ALTAR OF TRUTH

Wealth worship in Nigeria is not a benign cultural preference. It’s a revelation of the social values that actually matter. To speak honestly about the realities of Nigeria may sometimes come across as pessimistic, but the truth is that many Nigerians are living in what can only be described as a dire state of affairs. For a growing number of people, the only way out is either to acquire wealth or to leave the country entirely.

Nigeria offers very little to those without financial means. In a society where access to healthcare, sound education, security and even dignity is tied to wealth, poverty is more than just an economic condition, it is also a form of social exile. To be poor in Nigeria is to be at the mercy of a system built on exploitation and hardship. As a result, the country and everyday man has cultivated a collective obsession with money. It has created a monster with an insatiable appetite for wealth that feeds on the desperation of the masses. People are not only chasing a way out of suffering, but also yearning for access to the advantages, luxuries and frivolities paraded before them in an increasingly materialistic, globalised and digitalized world.

But as money and power continue to circulate among the hands of a privileged few, it poses the question: where does this ever growing desperation for wealth lead us, particularly in a nation that has taught its people that money is god?

Aisha Ayan is a University of Southampton Law graduate, cultural theorist, and social commentary writer. As a YouTube video essayist, her work examines society and culture in Nigeria and across its global diaspora. Her work explores themes of identity, class, pop culture, and the realities of modern day Nigeria.

Editor: Temi Ibirogba

This article is part of The Africa Center’s Third Spaces series, the recurring publications will offer social commentary and cultural analysis on topics pertaining to Africa and its Diaspora with the goal of addressing gaps in discourse. Third Spaces are submitted by members of The Africa Center’s community of thought leaders from across Africa and the African Diaspora. Follow @theafricacenter on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn to stay informed of new posts, and reach out to the editor to submit an idea for consideration.